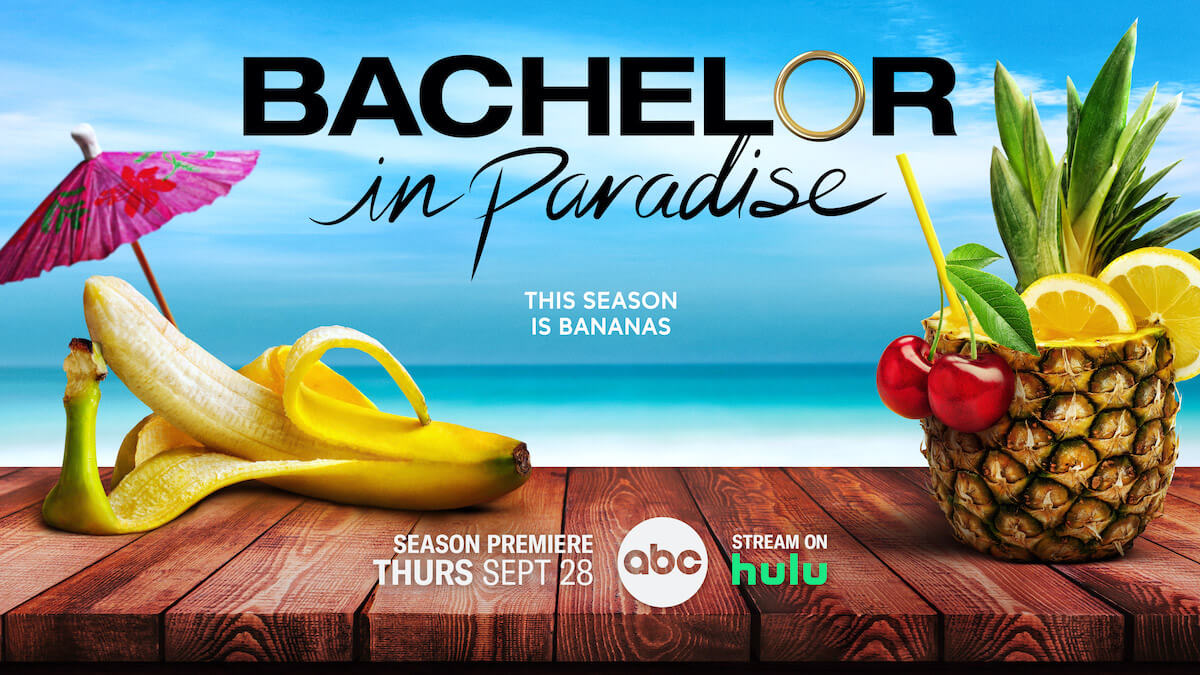

Bachelor in Paradise

Bachelor in Paradise

Bachelor in Paradise is a reality dating TV show that airs on ABC. First premiering in 2014, The Bachelor spinoff features former contestants from The Bachelor and The Bachelorette. The elimination-style reality show gives contestants a second chance at love in a secluded location in Mexico. The first season was filmed at the Casa Palapa resort in Tulum, Quintana Roo, Mexico. Every season since has been filmed at the Playa Escondida Resort in Sayulita, Vallarta-Nayarit, Mexico.

Visit the Bachelor in Paradise website.

- Debut Year: 2014

- Seasons: 9 and counting

- Network: ABC

- Filming Location: Sayulita, Vallarta-Nayarit, Mexico

- Where to Watch: ABC and Hulu

Visit the Bachelor in Paradise website.